My goodness. One would think based on these conversations that Oklahoma on fire again.

Brett, you are an incredible photographer and chaser and I have followed your work for a long time, and you're a damn good forecaster too. But look at your profile photo on here and tell me that "a smattering of fortuitous mesoscale accidents and 5% type days" - or, perhaps, a synoptically boring, poorly forced, highly capped setup with little aloft to speak of can't produce something amazing. Tell me that you haven't seen monsters under a big EML with a split flow regime, characterized by slow moving, sculpted mesocyclones that cycle in and out with little competition until the low level jet hits and everything goes nuts. You've seen it all in both the good and bad years, and given that I'm surprised to see you so down about a year that, despite your insistence otherwise, shares very little in common with bad - or good! - years of the recent past.

Here are the things that we

don't have that have marred most of my chase seasons to this point in one way or another:

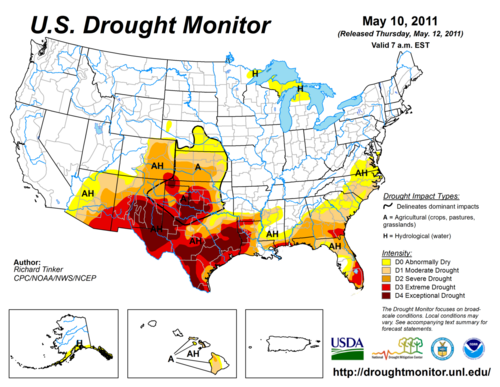

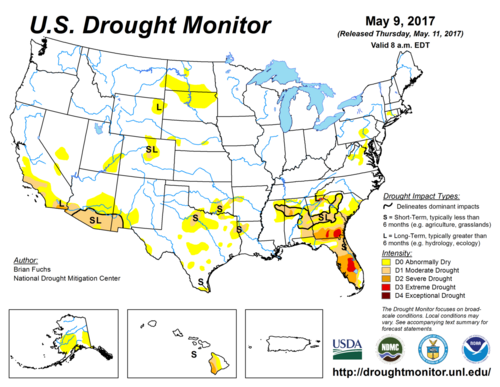

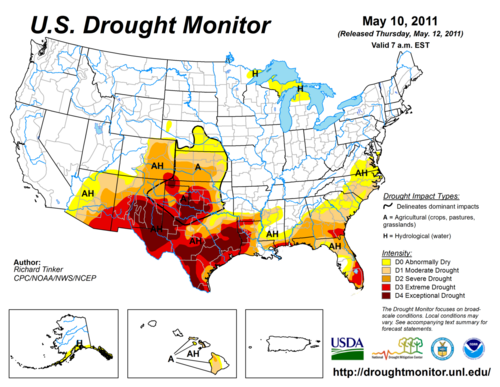

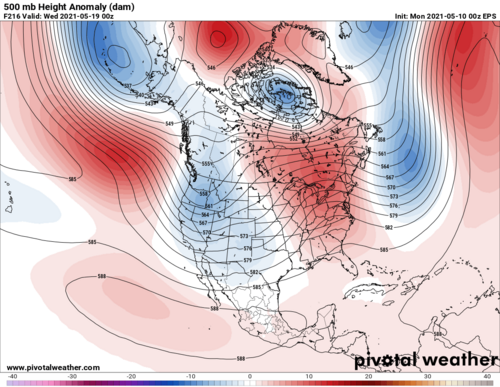

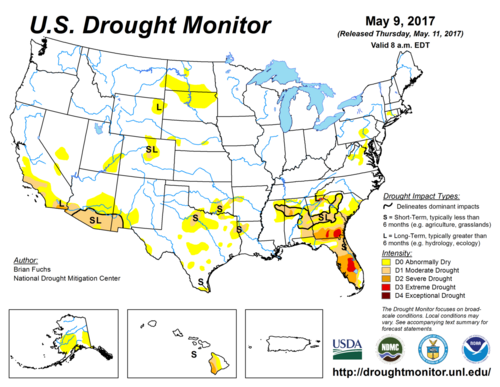

• Plains drought. ENSO may or may not be overrated (we can have that conversation another day), but it's not really arguable that this winter and spring hasn't behaved like the typical weak-to-moderate first Niña years of the past, which generally saturate the southeast and leave the plains begging for a drink. Take 2011, the one everyone was talking about this past winter, for example. Nobody wants the dryline mixed into Tulsa County, and so far we haven't had that! That's a huge plus, and that's why we have seen (and will continue to see) western Texas, western Oklahoma, and western Kansas drylines for the foreseeable future. This, for what it's worth, takes 2018's biggest problem off the table too.

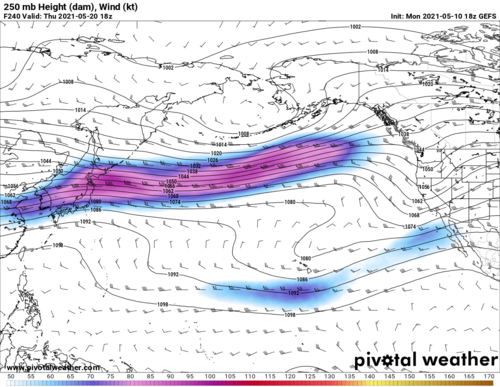

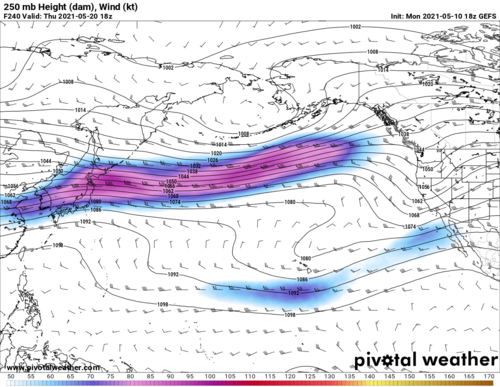

• Lack of flow aloft. Do you like jet extensions? I like jet extensions! We've had a couple (we're wasting a pretty nice one right now) and we're likely to have a couple more. This is where your 2020 comparison falls flat. While cutoffs and western ridging and all that nonsense can and probably will at some point take over, we've got some juice to kick the crappy patterns out of town. Does that guarantee greatness? Of course not. Does it assure you that these troughs will all amplify correctly, moisture will be there, and storms will form? Nope. Does it promise that the western ridge won't play like a Hall of Fame offensive lineman that doesn't let even the nastiest wave through? Sadly, no. But unlike last year, we're not waiting around playing the "if we can get some flow aloft" scenario. This year we've had it and we'll have it again.

Here are a couple of things that we

do have that, in my limited experience, can help us out:

• Big EML in the source regions. How much is too much? I don't know the answer to that, but if it stays in the desert, I'm okay with a little heat on my dinner plate. Sure, we might get a sunburn. I'm the palest white person on this planet, so I'll get a sunburn anyway. We might cap bust. We might watch our 18z 81/71 loaded gun soundings turn into 88/62 inverted V hailers by the time the dryline circulation pops off. But we might get dry air infused into our late evening storm, lighting up the land with bolts and stacking pancakes on pancakes. We might find our classic supercell a little less rainy and a little more hail-y, opening up the views from all kinds of angles even if we don't all have the stones to take baseballs (I don't!). We might find initiation waiting until 6 PM, storm maturing by 7 PM, backlit cone by 7:30 PM, and beers and crappy steaks at Applebee's in Salina by 9. Sorry for my obsession with drought, but another first Niña that got some attention was 2017, which was a great season if you liked being to your hotel before the sun went down. I don't. Initiation before noon is no bueno.

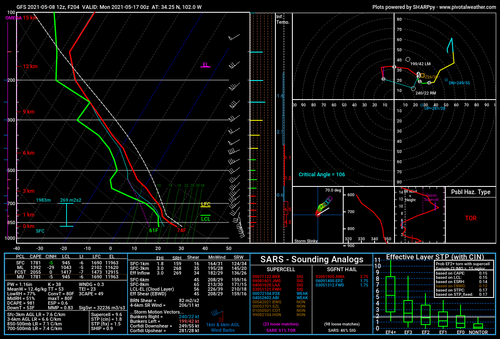

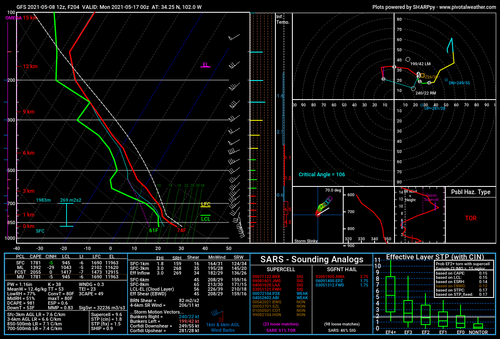

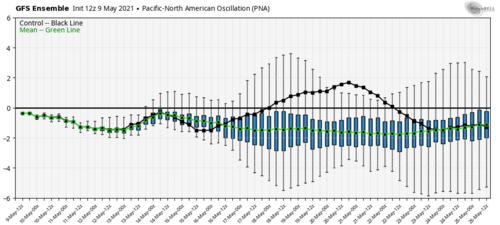

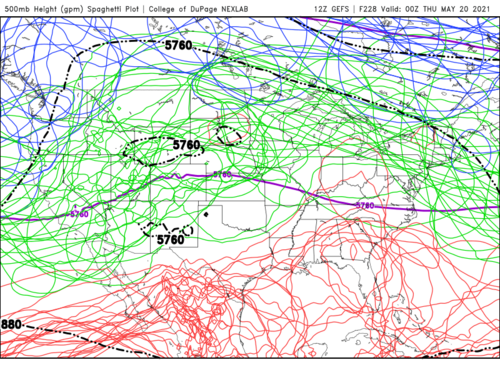

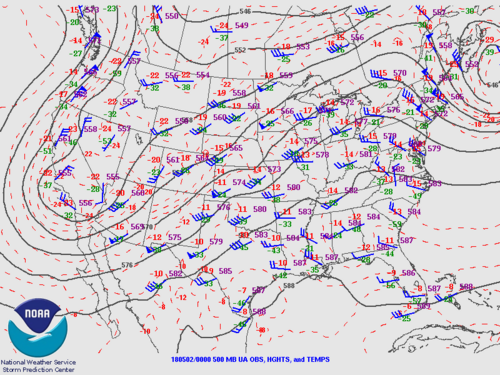

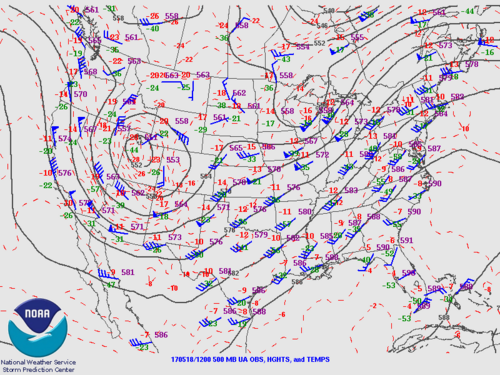

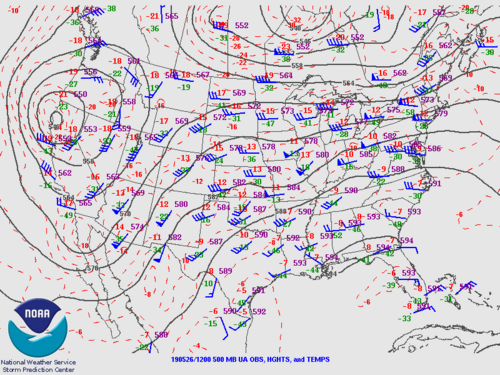

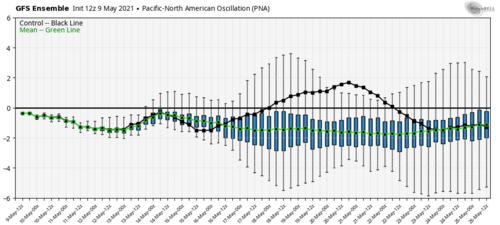

• Clueless models. Is this good? It's good if you only look at the operational GFS, which seems to be at least one of the prevailing methodologies among storm chasers as of late, for your daily dose of emotional distress. These things are performing awfully! (I don't think I could do a better job, but I'm also not a supercomputer funded by the US government.) Here are just a couple of examples that I stole from a few friends of mine today of the operational GFS in particular being incredibly bad:

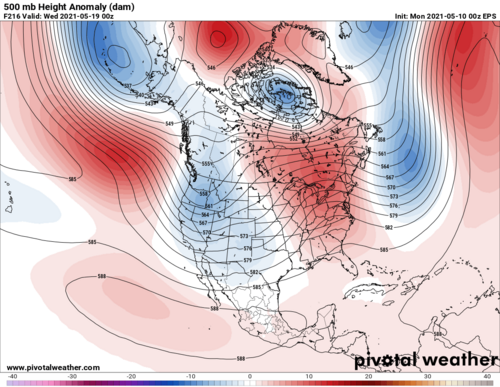

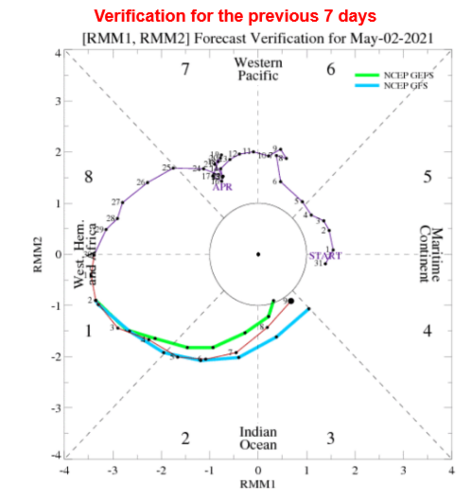

Is it odd that the control runs a higher PNA than its entire ensemble and falls well on the opposite side of zero as its ensemble mean? It should be.

Is it odd that the jet is supposedly heading into Canada and a western ridge is supposedly roasting Billings when the ensemble spaghetti plot could provide us more information if a three year old drew it with crayons and stuck it on the refrigerator? It should be.

I am hopeful that this post provides no new information to anyone because it shouldn't. Likewise, I don't intend to portray myself as some hyped up, wildly optimistic nutmeg who only looks at what he wants to see and blindly follows it, ignoring all signs to the contrary. I simply see signs of hope - and plenty of things that could yet trip us up, just as these Great Lakes troughs and scouring fronts already have. To me, that makes the doom and gloom hard to fathom. Why write off a season when we have seen so many seasons that appeared bad in numerous ways but had glimmers of light at the end of the tunnel turn out great? There's time left, and it is clearly possible that we use it in a favorable way going into the height of peak season in late May and into June. Maybe it works or maybe it doesn't, but there's no writing on the wall either way, and that alone is reason to keep your head up and eyes open in the coming weeks.