We’re coming up on the one year anniversary of this incident, but believe it or not, debate over the more controversial aspects is still ongoing. I know many of you are tired of this by now. I definitely am, but I was tasked with providing additional materials, and then also asked to present some of the latest findings at the Chicago AMS meeting back in March. I’d rather see results of my analysis used than fall by the wayside, so here it is for interested folks and for future reference. Anyone is welcome to use (or challenge) this material in their own publications.

Mesocyclone Structure Identification

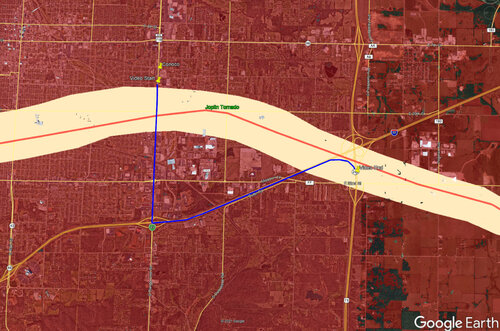

Much of the debate has centered on the storm’s evolution and mesocyclones: the tour group supposedly avoiding a “newly developing/large/primary” mesocyclone to their northwest that later goes on to spawn an EF4, while an old, occluded and smaller mesocyclone was hidden in a rainy downdraft to their southwest and harboring an “unknown” or “unexpected” EF2.

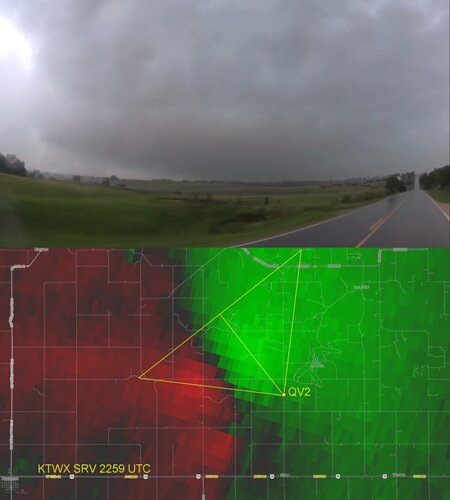

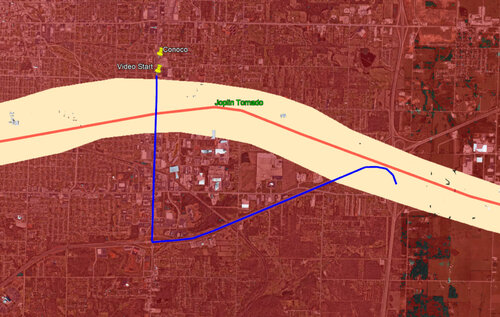

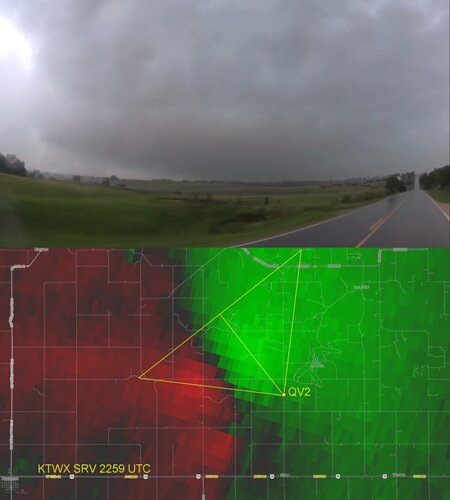

See pictures here courtesy Quincy Vagell showing a “rainy downdraft” (top) and what Jon Davies and Silver Lining staff have described as a “newly developing”, “large”, or “primary mesocyclone” (bottom) looking northwest a few minutes prior to the tour’s impact:

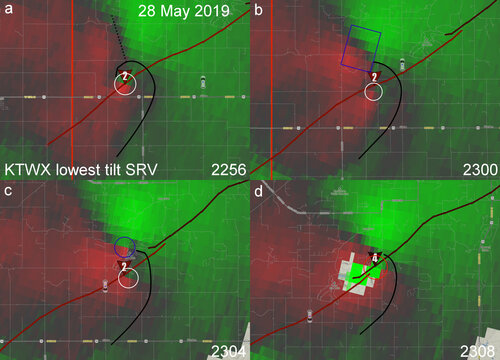

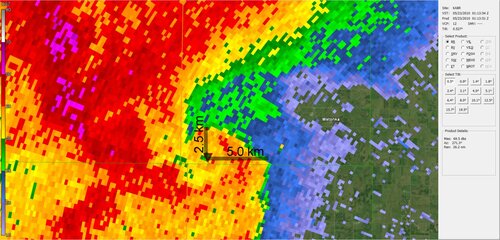

Quincy was shooting with a GoPro with a 90 degree field of view. We can plot his position and the field of view of his camera on top of the storm relative velocity from Topeka (KTWX) at the same time:

It’s understandable how chasers might envision the rounded rim of a mesocyclone in that dark cloud base. The velocity data shows that this would be a bad assumption, however. Quincy’s camera is not pointed toward the center of a couplet, but looking across the highest inbound velocities (brightest green pixels centered in yellow triangle). A portion of rear flank downdraft precipitation is visible on the left side of the video frame, and this is also indicated by the outbound velocities contained within the left side of the indicated field of view (red pixels inside yellow triangle). The camera is not pointing at a mesocyclone that is contained within that dark cloud base. It’s pointing at the inflow notch, inflow band, and inbound

half of what is a much larger mesocyclone. The rainy downdraft to the south is the outbound

half of the same mesocyclone.

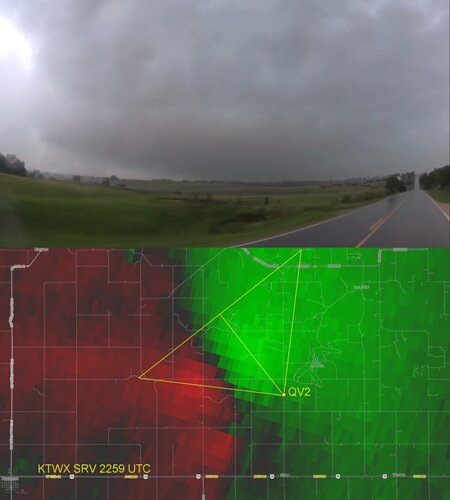

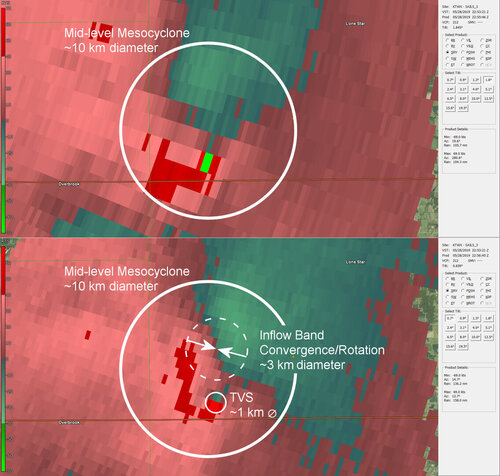

This was pointed out before, but the orientation of the larger, broad couplet to the west indicates a mix of convergence and rotation. These velocities are not fully indicative of the mesocyclone’s center or structure at this time. To get a better picture of that we need to look at some higher tilts on the Doppler velocity.

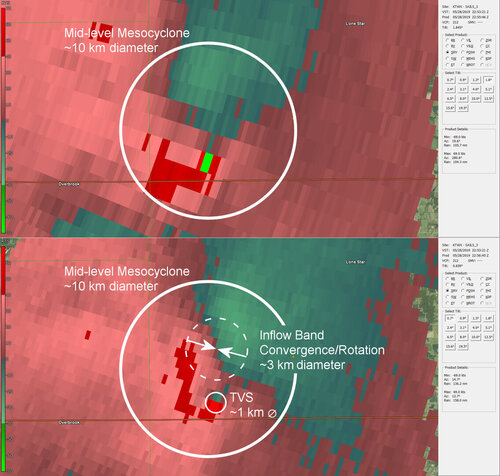

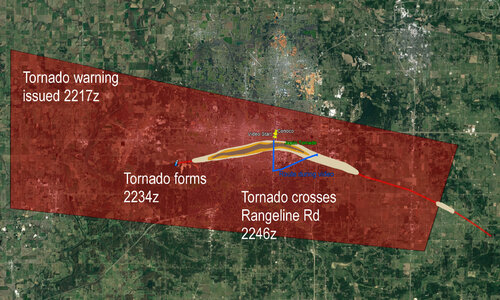

The top half of this graphic is the storm relative velocity at the 1.8 degree tilt (scan time and info shown on right panel), which at this range from the radar site is about 2500 meters above the surface. There’s a much larger rotational structure aloft here, and I think I and others have been overlooking the significance of this feature in previous attempts to dissect this event. The structure indicates a very large mid-level mesocyclone, at least 10 kilometers in diameter. It occupies several kilometers of the radar volume depth and is persistent from at least 10 minutes before the formation of the tour impacting Lone Star EF2 all the way through the Lawrence EF4. I had an exchange with a couple of the mets at NWS Topeka, and they brought it to my attention that this storm likely maintained a single, complex mesocyclone through the duration of both tornadoes, although ambiguities leave the storm’s evolution open to interpretation. The lowest-tilt storm-relative velocity scan is shown at bottom with identified rotational structures and their corresponding sizes. There’s a tornado vortex signature about a kilometer in diameter associated with the tour impacting Lone Star EF2. The couplet to the north is a mix of convergence and rotation, likely associated with the storm’s inflow band. The midlevel mesocyclone appears to be the dominant structure of the supercell, however, and is significantly influencing low-level cyclones of different scales, if not their causal mechanism.

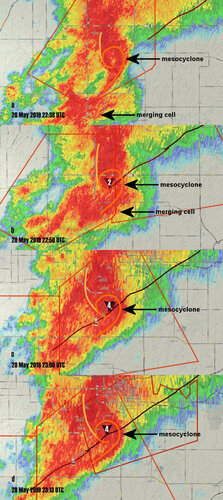

The structure of the midlevel mesocyclone is quite apparent in the reflectivity scans. This has been shown before, but I wanted to point out how well defined it was ten minutes before tornadogenesis of the Lone Star EF2 (top frame at 2238 UTC). There’s even a “donut hole” weak echo region in the center of the comma head. Notice a small cell encroaches from the south. This temporarily muddles up this comma head pattern on the reflectivity. NWS Topeka mets suggested this cell merger might have played a significant role in tornadogenesis of the EF2. The comma head pattern persists and on the same track line, however, suggesting both tornadoes were offspring of the same parent mesocyclone.

It was also implied that the Lone Star EF2 was somehow located in an unusual or unexpected part of the storm, as if it was much further into the RFD precipitation core and behind the RFD gust front than normal. Relative to the parent storm structure, however, the position looks quite typical to me, embedded in the center of a comma head shaped echo that, on this HP, corresponds with the supercell’s hook and flanking line region. I took a look at several other giant HP supercells, and on many of them, the tornado is even further behind the RFD gust front than the Lone Star EF2 was.

For example, after the 22 May 2010 supercell produced the Bowdle, SD EF4, the velocity couplet and embedded tornadoes were up to 5 kilometers behind the leading edge of the RFD gust front, whereas the Lone Star EF2 was about 2 kilometers behind the RFD gust front. It’s not so much that the tornadoes are much deeper into the RFD core than normal. It’s that the parent storms themselves are uncommonly large, with mid-level mesocyclones on the order of 10 km in diameter. Chasing around such giant and violent HP supercells requires extra care and spacing to stay out of the path of the “bear’s cage”, but these storms nonetheless exhibit recognizable patterns of supercell structure. If our goal in this discussion is to help chasers avoid future accidents, the emphasis should be on educating chasers to recognize these patterns of supercell structure and thus the most dangerous parts of the storm. Part of the problem may be that chasers are making some incorrect assumptions based off of conceptual diagrams of classic supercells, in that the RFD precipitation core is often depicted as west through south of, and distinctly separate from a tornado producing wall cloud. But main or primary tornadoes of supercells are characteristically at the tail end of an occluded gust front, behind the RFD gust front. Even on a classic supercell, the tornado is usually at least veiled in a thin curtain of RFD precipitation, and on an HP, it’s buried in it. We need to be educating chasers that on these giant, violent HP supercells, the RFD isn’t just a dangerous part of the storm. It’s the *most dangerous* part of the storm. It contains the supercell’s main tornado.

Tornado Merger Event

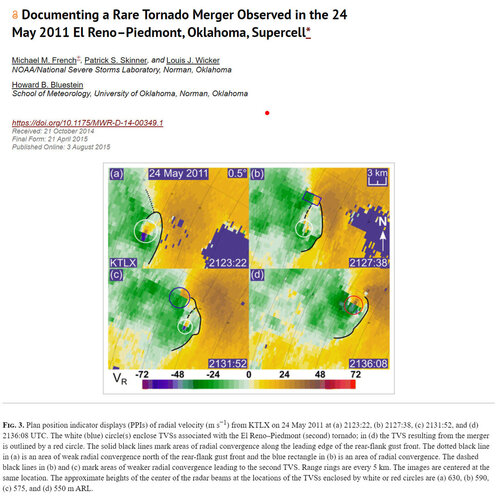

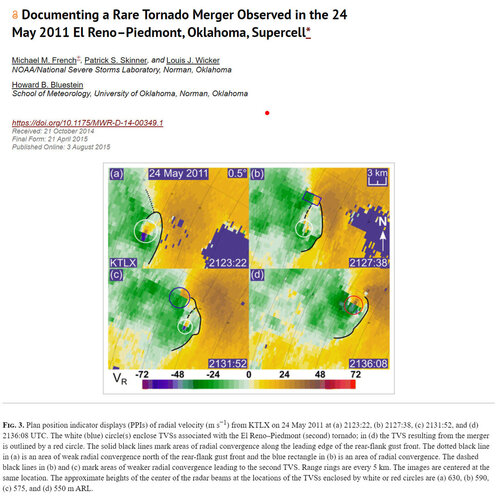

Much additional attention was put on the possible merger of two tornadoes just after the SLT impact incident. If the structure to SLT’s northwest before they turned around wasn’t a newly developing, primary mesocyclone, then the question becomes what is behind the development of the new tornado in the merger event? A really good analog for the 28 May 2019 supercell and tornado merger event may be the 24 May 2011 El Reno-Piedmont supercell and associated EF5 tornado. A paper by Michael French and others documents the likely merger of a satellite tornado with an ongoing tornado to the south on an HP supercell:

https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/10.1175/MWR-D-14-00349.1

https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/10.1175/MWR-D-14-00349.1

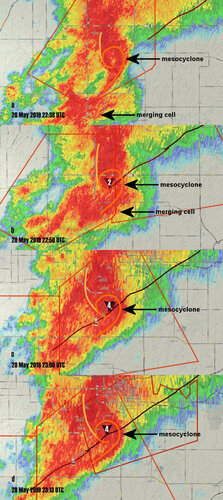

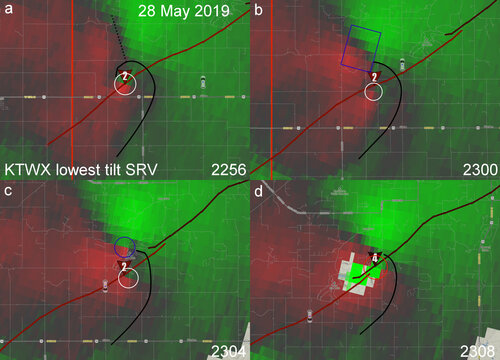

There is a strikingly similar pattern in the above velocity sequences from the two storms (and aloft as well as shown later).

In both sequences:

a. An ongoing, mature tornado (white circle) is behind a well-defined RFD gust front (roughly approximated by solid black line), with a convergent inflow band extending to the north northwest off the top of the RFD gust front (dotted black line). Note that, on both events, the elevation of the radar beams is approximately a kilometer above the ground and likely above the storm’s cloud base, and so missing low level detail like that of the RFD gust front.

b. Convergence on the inflow band intensifies and then begins to transition into a couplet with a mix of rotation and convergence (blue rectangle).

c. The new couplet moves storm relative south along the inflow band, and is drawn into the back rim of the midlevel mesocyclone. It tightens into a focused rotational couplet on the RFD gust front at about the time tornadogenesis occurs (blue circle).

d. The developing tornado, turning left like a satellite around the back rim of the midlevel mesocyclone, apparently merges with the ongoing tornado. This happens behind the RFD gust front while the convergent inflow band to the north northwest persists.

It’s interesting that this sequence occurs over the same amount of time in both storms: ~12-13 minutes.

SLT initially claimed they were avoiding a mesocyclone to their northwest and then were impacted by a satellite tornado of that mesocyclone. The irony in this, if the interpretation of the above sequence is correct, is that the area to SLT’s northwest would be a satellite producing location, and their maneuver to avoid this part of the storm instead caused them to drive into the mesocyclone’s main tornado.

Roger Edwards has some shots of the 24 May 2011 merger in the above paper. But there’s also this notable video from the event:

That was shot from just west of the intersection of US 81 and Darlington Rd. from about ~2119-2131 so it’s before the paper’s merger sequence, but I believe it shows the same process in detail. A funnel/circulation/small tornado appears to form on the convergent inflow band where it intersects the RFD gust front before being drawn in and perhaps merging with the ongoing EF5 behind that RFD gust front. The chaser correctly identifies the inflow band structure, and that the funnel/tornado is behaving more like a satellite, even though he doesn’t have a visual on the main tornado due to it being rain wrapped in the RFD core. The chaser is in the inflow notch in a position not unlike SLT’s position on the Lone Star-Lawrence storm, so making these identifications was crucial from a safety standpoint. Misidentifying the inflow band structure, the funnel as a main tornado, or its motion could have sent the chaser on an incredibly dangerous southbound escape route across the path of the hidden EF5.

Also making 24 May 2011 a good analog to study are the storm chaser accidents that occurred. Minutes before these merger sequences, Chris Novy repositioned two miles south in an attempt to clear the path of the tornado. He was then overtaken by what he thought was just RFD precipitation, and was sideswiped by the tornado with significant damage to his vehicle. David Demko and crew also had a harrowing close call as they raced the tornado across its path after misjudging its motion and the roads:

This is not to scold these chasers. Instead they should be commended for actually taking responsibility for their actions, and making them examples from which others can learn.

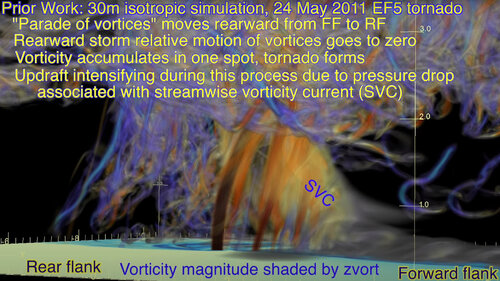

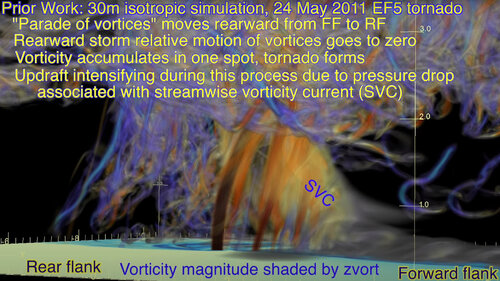

Dr. Leigh Orf’s supercomputer modeling of the same 24 May 2011 supercell sheds a lot of light on the structure and processes at work here:

The structure of the inflow band running north of the tornado is very prominent in the animation and appears to be associated with what Dr. Orf has identified as the “streamwise vorticity current”. You can also see columns of vertical vorticity beneath the SVC feeding directly into the main tornado. In some of Dr. Orf’s other animations it looks like some of these manifest as weak tornadoes with condensation funnels that hook left into the main tornado like infalling satellites. I think Dr. Orf presents a compelling theory and great depiction of what we’re seeing in the above 24 May 2011 video and also the sequence that occurred with the 28 May 2019 Lone Star-Lawrence merger event.

From:

We saw this behavior on other giant, violent HP supercells. Many of you contributed footage to the crowd sourced study of the 2013 El Reno storm. Similar infalling satellites forming on the inflow band portion of the storm, north northwest of the main tornado, were documented by storm chasers. Please see:

And again we saw it on the above referenced 22 May 2010 Bowdle, SD supercell. A paper by Dr. Bruce D. Lee and others describes the motion of a smaller tornado that preceded the Bowdle, SD EF4. It becomes displaced from its track, likely by an RFD surge, and then ambiguously merges with the developing EF4 while new circulations form to the north northwest and orbit cyclonically around the mid-level mesocyclone like satellites. Please see:

https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/full/10.1175/MWR-D-11-00351.1?mobileUi=0

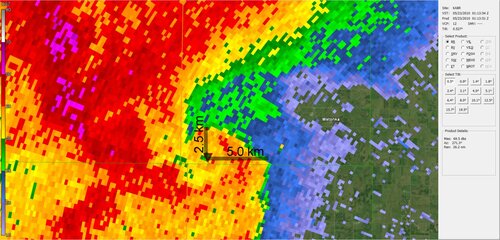

Looking aloft on the 24 May 2011 storm you again see this giant mid-level mesocyclone:

The 1.8 degree tilt is shown here, the radar beam approximately 2.5 km above the surface. This rotational structure is in the same location aloft and is the same size as on the 28 May 2019 Lone Star-Lawrence storm. I think that’s the common theme on all of these storms. 22 May 2010, 24 May 2011, 31 May 2013, and 28 May 2019 all exhibited these giant mesocyclones of 10 km or more in diameter within a violent HP supercell, and they all exhibit this infalling satellite behavior on the inflow band. These giant, violent HPs are the storms that are causing storm chaser accidents, injuries, and fatalities. They’re more common than people think too. It’s critical that we understand these events or we’ll continue to see additional accidents.

The main takeaway to all of this is that the structure centered in this view is not representative of the storm’s “primary mesocyclone” or main/primary tornado producing location. It’s incorrect to identify this structure as such, and this is probably the result of misinterpretations of both visual storm structure and Doppler radar velocity. Such misinterpretations could have directly contributed to the SLT incident, erroneously prompting chasers to flee towards what in fact was a more dangerous part of the storm. Publications and blog posts that reinforce these misinterpretations may contribute to future accidents as well, so they need to be corrected. Instead it should be stressed that the area under the inflow band, while still dangerous and capable of producing tornadoes, poses a *secondary* threat to chaser safety. The *primary* threat to chaser safety and the most likely location for a significant tornado is on and behind the RFD gust front, which is where both tornadoes on the 28 May 2019 Lone Star-Lawrence supercell occurred. Indeed, it’s the characteristic location for a significant tornado on supercells in general. And on a giant, violent HP that means the tornado is probably going to be hidden within at least a couple kilometers of rain. Extra emphasis needs to go into educating chasers against blindly punching the RFD core because apparently some do not realize the risk they are taking, and there seems to be confusion about this from even some of the most experienced chasers and meteorologists.