This might be of interest, as it talks about a shift this year in the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone meaning storms coming out of Africa are doing so over less favourable waters.

A rare rainfall event is starting in the Sahara desert, signaling a potential change in the Earth's weather system.

www.severe-weather.eu

Funny you mentioned this. This pattern giving the Sahara significant rainfall is likely why the Atlantic has been largely

shut down so far. See below post I did on another group yesterday.

-----

So many are wondering, "where are all the hurricanes in the Atlantic?"

This is a valid question, and given all the hyperactive forecasts, a serious

one.

Here's what we have that says it should be very active now for hurricanes

in the Atlantic.

1) Record sea surface temps anomalies/oceanic heat content

2) Reduced vertical wind shear

3) Northward shifted and enhanced African monsoon

4) Neutral ENSO, trending towards La Nina.

So large-scale factors are favorable . However, one small detail is off,

which seems to explains things -- the African monsoon trough, which

supplies the bread and butter of disturbances/waves that eventually

develop into TCs in the Atlantic, has been *too* far N. This puts its

axis into the Sahara Desert. So even though rainfall is above avg in

the Sahara Desert, this area is still *far* too dry for robust MCSs/MCCs

to develop, which end up moving off the west African coast, and

provide the initial seeds for TC development.

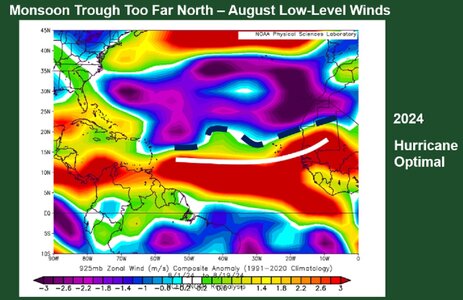

Look at the graphic attached. It shows the zonal low-level wind

anomalies for August in the Atlantic, and the sharp gradient is the

axis of the monsoon trough (the black dashed line). The white line

is the ideal position of the monsoon trough needed for MCSs/MCCs

over the sub-Saharan region and ern Atlantic that eventually form into

TCs.

So the monsoon trough is a couple hundred miles too far N, and that's

all it has taken to squash overall TC activity big time, w/ only 5 named

storms so far, far below the hyperactivity expected.

It seems conditions two months ago were ideal, and we got record

Hurricane Beryl, but a single intense hurricane does not make a big

season, or mean what we expected throughout the season occurred!

We are now in the most climatologically active part of the hurricane

season, and nada, and not much forecast at all in the next week.

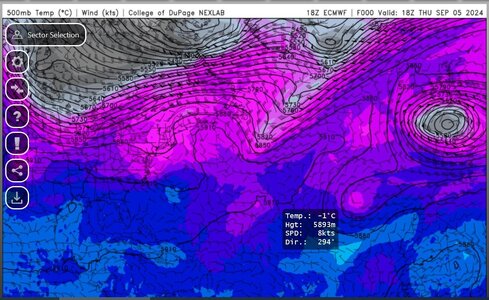

Just looking at the operational GFS/ECMWF/GDPS the last 5 days, they are not

consistent. One run has a hurricane a 5-8 days out, then the next run loses

it, then it comes back, and loses it again next run. It's been like this for all 3

models.

I know ensembles are better, however, we are taking within 10 days, and from

my empirical observations following the operational runs and TC development, if

the pattern is truly favorable, they will show good consistency on developing a

particular disturbance(s) within 10 days, or at least one model will. The GFS does

this most often, and still seems to have a problem being too aggressive day 7 and

beyond, but even this model is lacking given its bias in the longer ranges. If the

GFS is this "tame," given its TC bias, what does that say about the synoptic

environment as a whole in the Atlantic? These global models must be detecting

something that is putting the brakes on things?!

The current wave now in the Caribbean that NHC has been tracking for the last 5

days, it has stayed at 0/40 chance of development? It is the *peak* of the season,

and this would be lame in a normal season forecasted, but given the hyperactive

forecasts?!

This doesn't mean the season is over w/ no major hurricanes (2020

was back-ended with a lot of major hurricanes), but shutting down

the prime time of the season usually severely limits total seasonal

activity, which is what matters in the end. I don't see how now the

forecasts for 20-25+ named storms that all are going for are going to

verify.

And the record high Atlantic ocean temps, being in record territory, this

may be actually providing a negative feedback, *detrimental* to TC

formation. How?, a warm ocean is going warm the atmosphere above

it, and air warms faster and easier than water. A "hotter" atmosphere is

often not favorable for widespread deep convection b/c warm temps at

mid-levels inhibit CU growth. In addition, the warmer atmosphere

becomes drier, and this can promote even more warming (i.e. dry air heats

up easier than moist air), strengthening the capping temp inversion aloft,

which suppresses deep convective development further. See the negative

feedback here? Not intuitive and goes against the typical human thought

process correlation = causation directly.

Ocean temps are only one part of the equation for TCs. What goes on the

atmosphere is very important. These record high Atlantic ocean temps we

have never witnessed in the modern age are apparently or may be a range

that actually inhibits tropical cyclone formation?! Imagine that!

(end of original post)

-----

This is why treating the atmosphere linearly and "dumbing complex processes down" to catchy

quips and statements is severely flawed, and really an insult to the the field of meteorology, and all

sciences for that matter. Things do not work in a 1-2-3 simple correlation = causation way in

something as complex as the Earth's system and how it responds to warming. Positive and

negatives feedbacks are many, and this makes the line "warming ocean temps due to climate

change will make all tropical cyclones worse everywhere across-the-board" vapid and

disingenuous. As said above, ocean temps are only one part of the equation for TC genesis

and maintenance.

In the current season's case, we can't even get decent disturbances off Africa that eventually

develop into TCs! So the "seeds" of TCs are taken out. All the warm ocean and favorable

atmospheric conditions mean nothing you can't get a TC to form in the first place to take

advantage such conditions!

It goes further than the classic long-tracked Cabo Verde hurricanes being absent. Many tropical

waves don't develop until later in the Caribbean, GOMEX, or western Atlantic, so this explains

in part why even these areas are so quiet. And going even further, many tropical waves in the

Atlantic that never develop cross Central America, and then develop into TCs in the EPAC, so this

explains in part why the EPAC has been below avg so far this season.

So you see how *one* smaller-scale phenomena (the position of the monsoon trough) has huge

downstream impacts, despite the overall pattern favorable for Atlantic TCs, and this one of

many examples that we have seen that show how complex things are and we are far from having

both normal climate variances and climate change "all figured out" and "the science is settled."

Empirical observations override what models "say" and forecast.

More people should be doing this (below emoji).