Boris Konon

EF4

Post on the current TC season, not just for the Atlantic, but for the entire

Northern Hemisphere so far, along w/ some deeper musings.

Through August 12, the Northern Hemisphere is well below normal season-to-date

18 named storms so far (normal is 24 season-to-date), 6 hurricanes/typhoons

(normal is 12), and 2 major hurricanes/typhoons (normal is 6). Total

accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) is only 52% of normal season-to-date.

The eastern Pacific is off to one of it slowest, if not slowest, starts to a season

on record. Why don't we hear about this? It is an extreme, just on the other end

of the atmospheric spectrum. If you are going to report on weather events, you

can't just omit things that deflate a particular narrative. And it have been observed

when the Atlantic is very active for TCs, the northern Pacific in its season is less

active than typical.

Yes, the Atlantic has been active, but only in some ways. Basically, Hurricane

Beryl is the only anomaly so far and accounts for almost all the high numbers

for the Atlantic season-to-date (named storm days, hurricane days, major

hurricane days, and ACE). Not saying Beryl was not a major anomaly,

but one storm does not reflect the entire season or season-to-date

in the larger climatology picture.

For instance, take the most active Atlantic hurricane season overall, 2005.

Through August 12, we already had 8 named storms, 4 hurricanes, and 2 major

hurricanes (one strong Cat 4 and a Cat 5). This blows away (no pun intended!)

the 2024 season-to-date. Since we have the warmest Atlantic ocean temps on

record, and conditions in the atmosphere are said to be so favorable, where is

this hyperactivity for tropical cyclones in the Atlantic?? Ernesto's disturbance began

in the eastern tropical Atlantic, why did it take until getting close to the Lesser Antilles

for it to become a TC? Given the said very favorable overall conditions that does not

jibe well. Why didn't Debby undergo rapid intensification in the well above avg

GOMEX water temps before making landfall in the FL Panhandle?

2005 was a true hyperactive Atlantic season, not only total, but it started early and

never stopped, w/ active named storms most days July-Oct. We are not seeing that all

all in 2024.

Now, it is still early overall, but a couple things on that. 1) All forecasts are

going for 20+ named storms in the Atlantic this season, and two have 25+

w/ one 33 and 2), none of the global models show any tropical storm or

hurricane development in the Atlantic the next 10 days, which brings us to 8/26.

We have 5 named storms so far. Although 15 more named storms after 8/26

has happened before, and will get us to 20 for the season, 20 or more named

storms for the true hyperactive forecasts (25+), that's going to be tough. Not

saying it can't happen, but the Atlantic only has so much room and it actually

can get too "crowded" w/ storms at times (happened in 2023 and other years).

TCs need room around them to develop and esp. to get intense, otherwise, they

will inhibit each other's full potential. So even though you can have 4 named

storms at once, that tends to be the limit based on past very active seasons. And

even in the most active seasons, there are cycles (MJO) where conditions overall

wane at times for tropical cyclone development in the entire Atlantic, so it can't

be full throttle to the max all the time in a season (2005 and a few other seasons

going back to 1851 are close).

So I have presented the hard facts above. What am I getting at? As much as

it may be portrayed this way these days and sounds counter-intuitive, the

atmosphere and climate are *not* linear. In a global sense, avg mean temps

warmer does not necessarily mean all storms and other impactful weather get

worse. Some things get better/less common or intense. Now, one can debate

the balance of that plus/minus here, but that's a different issue. I am talking

about the all too often A+B=C ideology. The global system is about as far as

you can get from that, and I get it, things need to be simplified and worded for

general communication to the public, but some things simply can't be summed

up in a few words or pithy quips or statements! That's the nature of many

sciences, like it or not.

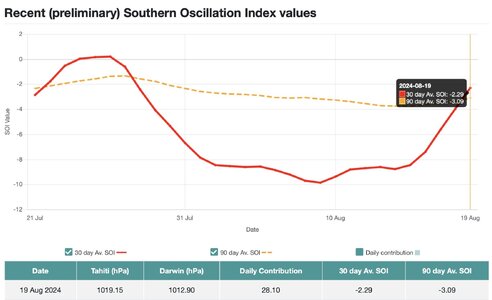

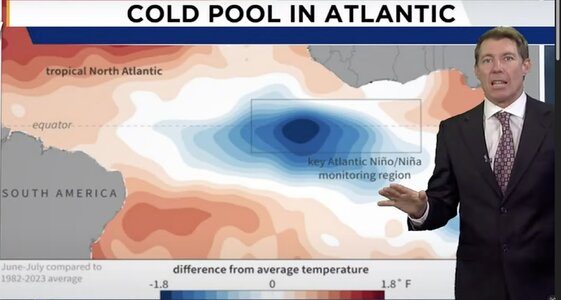

Going down to a more localized level -- strong El Nino in 2023. Typically,

strong El Nino suppresses Atlantic hurricane activity big time. 2023 though

bucked this and was quite active (a record for strong El Nino present). Now,

in 2024, we have La Nina, and this typically favors active Atlantic hurricane

seasons. Given the non-linear nature of the atmosphere, and a wildcard we have

not experienced in the modern era w/ an excess of water vapor present in the

stratopshere since 2022 from the very large Hunga-Tonga volcanic eruption,

who is to say this can't work in reverse, meaning despite La Nina, the Atlantic

ends up not as active as expected? This is on top of record warm ocean temps

in the Atlantic, which *should* mean hyperactivity (some going for the biggest

season on record). Yet go back what I said above w/ the Atlantic hurricane

season so far and how it compares to other seasons. It does not fit what

has been forecast or said (hyped) so far. Long way to go still, but food for

thought.

The Atlantic I think still will end up an above normal year, but there is valid

concern IMHO it may not live up to its hype or hyperactivity. Just b/c past

history, our knowledge, and weather/climate models say this *should*

happen, does not mean it will all the time. Again, the non-linear nature of the

atmosphere, and a limited, very reliable and detailed data on the

weather/climate as to what can happen, says that things we think can not or

should not happen, can and will, and there is nothing saying we can't be

totally off or completely wrong in what we think for some things.

There is a saying, "the more you know, the more you realize you *don't* know!"

and almost all of us have sensed this or had an epiphany at one time or another

in our lives! This is a good thing overall, and it motivates us to push forward and

learn more, and not rest on our laurels.

I'll say again though, that does not mean the current Atlantic hurricane season

will not be very active, and of course, does not mean we won't get one or more

major hurricane landfalls that are very high impact, but I am looking at the

grander picture here, as in what we have forecasted and expect vs. what

actually has happened so far/happens. Sure, this may not grab headlines

or is too pedantic, but it is not something that should be ignored or

discarded b/c it isn't "liked" or "popular."

Northern Hemisphere so far, along w/ some deeper musings.

Through August 12, the Northern Hemisphere is well below normal season-to-date

18 named storms so far (normal is 24 season-to-date), 6 hurricanes/typhoons

(normal is 12), and 2 major hurricanes/typhoons (normal is 6). Total

accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) is only 52% of normal season-to-date.

The eastern Pacific is off to one of it slowest, if not slowest, starts to a season

on record. Why don't we hear about this? It is an extreme, just on the other end

of the atmospheric spectrum. If you are going to report on weather events, you

can't just omit things that deflate a particular narrative. And it have been observed

when the Atlantic is very active for TCs, the northern Pacific in its season is less

active than typical.

Yes, the Atlantic has been active, but only in some ways. Basically, Hurricane

Beryl is the only anomaly so far and accounts for almost all the high numbers

for the Atlantic season-to-date (named storm days, hurricane days, major

hurricane days, and ACE). Not saying Beryl was not a major anomaly,

but one storm does not reflect the entire season or season-to-date

in the larger climatology picture.

For instance, take the most active Atlantic hurricane season overall, 2005.

Through August 12, we already had 8 named storms, 4 hurricanes, and 2 major

hurricanes (one strong Cat 4 and a Cat 5). This blows away (no pun intended!)

the 2024 season-to-date. Since we have the warmest Atlantic ocean temps on

record, and conditions in the atmosphere are said to be so favorable, where is

this hyperactivity for tropical cyclones in the Atlantic?? Ernesto's disturbance began

in the eastern tropical Atlantic, why did it take until getting close to the Lesser Antilles

for it to become a TC? Given the said very favorable overall conditions that does not

jibe well. Why didn't Debby undergo rapid intensification in the well above avg

GOMEX water temps before making landfall in the FL Panhandle?

2005 was a true hyperactive Atlantic season, not only total, but it started early and

never stopped, w/ active named storms most days July-Oct. We are not seeing that all

all in 2024.

Now, it is still early overall, but a couple things on that. 1) All forecasts are

going for 20+ named storms in the Atlantic this season, and two have 25+

w/ one 33 and 2), none of the global models show any tropical storm or

hurricane development in the Atlantic the next 10 days, which brings us to 8/26.

We have 5 named storms so far. Although 15 more named storms after 8/26

has happened before, and will get us to 20 for the season, 20 or more named

storms for the true hyperactive forecasts (25+), that's going to be tough. Not

saying it can't happen, but the Atlantic only has so much room and it actually

can get too "crowded" w/ storms at times (happened in 2023 and other years).

TCs need room around them to develop and esp. to get intense, otherwise, they

will inhibit each other's full potential. So even though you can have 4 named

storms at once, that tends to be the limit based on past very active seasons. And

even in the most active seasons, there are cycles (MJO) where conditions overall

wane at times for tropical cyclone development in the entire Atlantic, so it can't

be full throttle to the max all the time in a season (2005 and a few other seasons

going back to 1851 are close).

So I have presented the hard facts above. What am I getting at? As much as

it may be portrayed this way these days and sounds counter-intuitive, the

atmosphere and climate are *not* linear. In a global sense, avg mean temps

warmer does not necessarily mean all storms and other impactful weather get

worse. Some things get better/less common or intense. Now, one can debate

the balance of that plus/minus here, but that's a different issue. I am talking

about the all too often A+B=C ideology. The global system is about as far as

you can get from that, and I get it, things need to be simplified and worded for

general communication to the public, but some things simply can't be summed

up in a few words or pithy quips or statements! That's the nature of many

sciences, like it or not.

Going down to a more localized level -- strong El Nino in 2023. Typically,

strong El Nino suppresses Atlantic hurricane activity big time. 2023 though

bucked this and was quite active (a record for strong El Nino present). Now,

in 2024, we have La Nina, and this typically favors active Atlantic hurricane

seasons. Given the non-linear nature of the atmosphere, and a wildcard we have

not experienced in the modern era w/ an excess of water vapor present in the

stratopshere since 2022 from the very large Hunga-Tonga volcanic eruption,

who is to say this can't work in reverse, meaning despite La Nina, the Atlantic

ends up not as active as expected? This is on top of record warm ocean temps

in the Atlantic, which *should* mean hyperactivity (some going for the biggest

season on record). Yet go back what I said above w/ the Atlantic hurricane

season so far and how it compares to other seasons. It does not fit what

has been forecast or said (hyped) so far. Long way to go still, but food for

thought.

The Atlantic I think still will end up an above normal year, but there is valid

concern IMHO it may not live up to its hype or hyperactivity. Just b/c past

history, our knowledge, and weather/climate models say this *should*

happen, does not mean it will all the time. Again, the non-linear nature of the

atmosphere, and a limited, very reliable and detailed data on the

weather/climate as to what can happen, says that things we think can not or

should not happen, can and will, and there is nothing saying we can't be

totally off or completely wrong in what we think for some things.

There is a saying, "the more you know, the more you realize you *don't* know!"

and almost all of us have sensed this or had an epiphany at one time or another

in our lives! This is a good thing overall, and it motivates us to push forward and

learn more, and not rest on our laurels.

I'll say again though, that does not mean the current Atlantic hurricane season

will not be very active, and of course, does not mean we won't get one or more

major hurricane landfalls that are very high impact, but I am looking at the

grander picture here, as in what we have forecasted and expect vs. what

actually has happened so far/happens. Sure, this may not grab headlines

or is too pedantic, but it is not something that should be ignored or

discarded b/c it isn't "liked" or "popular."