I do think that, in spite of the information available, people simply aren't going to inconvenience themselves to pay attention to what's upcoming. Lead times by and far are better than they've ever been, yet after every high end event (that was forecast multiple days out) we inevitably see someone being interviewed on TV saying "we had no warning."

To his point about "untrained" spotters, i would hope that he meant to include public safety in that criticism. I know of know major police department or sheriff's office that has their officers/deputies go through any formal training, and for firefighters, that seems to be contained primarily within volunteer departments. That is something I've thought of for some time, and were I asked (which I think is unlikely), I would be more than happy to put something together to help remedy that.

Drew makes a couple of important points. Last one first: My nephew graduated from the Kansas police academy. He, and later a representative, confirmed that police in Kansas get zero training on weather-related events. I had a conversation with that representative about adding training and they simply are not interested. That is fine, but we in weather science should realize that their reports are, at best, of equal value to the public-at-large's.

As to lead time, I believe the NWS is making a huge mistake with its oft-stated "one hour of lead time" for tornadoes. This goal is again included in the TORNADO Act before the U.S. Senate. I believe the one-hour is solely a justification for another mistake: Warn-on-Forecast.

Suppose you are home, at the office, or school: how long does it take you to get to shelter? In 99% of these circumstances it is 30 seconds to 2 minutes. Dr. Kevin Simmons' peer-reviewed research shows that fatalities go

up with lead times of more than 15 to 18 minutes. My speculation as to "why" is that people will only stay in bathtubs or closets for so long.

The all-too-frequent, "we had no warning" has nothing to do with lead times. It is either, 1) an excuse for not paying attention or, 2) rejection of personal responsibility.

A dozen years ago, we had a simple tornado warning system that worked well. We are now laying layer upon layer of complexity (see:

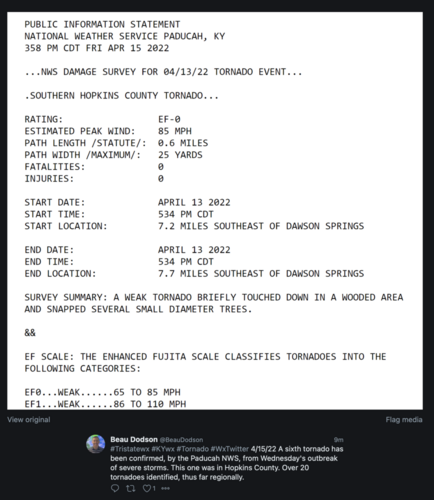

Bad Science: Meteorology's "Onesie" Problem ) on the tornado and severe thunderstorm warning system and then are surprised it is failing: lead-times halved and PoD's dropping from 73.3% to 59.2%, even with calling 25 yard area of broken tree branches a "tornado" to verify a warning.

Yet, when something is proposed to improve the system like gap-filler radars, the NWS rejects it (

https://www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2020/11/21/radar-gaps-weather-service/ ). In 2017, Congress asked me to provide a list of locations for 20 gap-filler radars and the northern Arkansas - southern Missouri gap was #10 on the list.

NOAA's senior management has no one who knows anything about weather. I don't see that changing anytime soon.

So, the only solution I can think of is a National Disaster Review Board (modeled after the NTSB) that could also solve the very serious problems with FEMA (ask anyone in Lake Charles about them) and other U.S. disaster forecast and response agencies.